Decaying Belgian colonial era structures speak to the area’s history of mining, and to Congo’s struggles with outsiders who vied for its riches. Lulingu was a central site for Belgian colonial mining operations until the 1960s. After independence, the Belgians returned as contractors and remained in the area until 1988. It is one of the two biggest points in the province for cassiterite mining, and was thus a key site for mining during Belgian colonial times. The town still benefits from certain infrastructure set in place by the colonial enterprises, such as very basic electrical power lines and a river dam. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Raia Mutomboki ranks include women and minors, allegedly enlisted voluntarily. Mari, now 18 years old, joined the Raia Mutomboki as a soldier when she was 16 years old. At the time she had already lost her entire family to the conflict. She soon married a fellow soldier whose family had suffered a similar fate. They now have a son together. Dec. 27, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government administrator, hosts a town meeting alongside traditional and Raia Mutomboki leaders inside a decayed building from the Belgian colonial era. The Raia Mutomboki insist they should not be labeled “rebels” like other armed groups operating in Congo, citing that they have not interfered with the work of government officials in their territory. Dec. 28, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Raia Mutomboki fighters gather, wearing leaves for camouflage, after going on a patrol through Lulingu’s surrounding areas. The group claims that they derive their power from the Dawa, a magical bracelet worn around their upper arms. The power comes from Kimbirigiti, a forest spirit that they invoke through their elders when there is an enemy. As long as they respect the rules not to rape or steal, Kimbirigiti will render them invincible to their enemies. Dec. 27, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A young boy stands by a reservoir in the dense jungles just outside Lulingu, a remote village in South Kivu. The jungles are littered with mining sites and various armed groups. Dec., 2013. South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Seated in her office, Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government Administrator, explains her position vis-a-vis the Raia Mutomboki. Herself a victim of the abuses of both the Interahamwe and the Armed Forces of the DRC, she says she is happy with the security the RM have brought to the area. Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Graffiti on the walls of the home of Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government Administrator, testify to a time when FARDC soldiers forcefully occupied her home for over a year, throwing out her children. At the time she was hospitalized in Goma due to injuries from a moto accident. After they were defeated by the RM, the FARDC left Henriette's home and the area, first looting all of Henriette's valuables that were in her home. Jan. 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Widow Madelaine Kapinga stands outside of her makeshift home in a part of Lulingu town that is occupied by people displaced by the conflict. Her story is not an uncommon one in the area, where most have lost family to massacres committed by the Interahamwe or in subsequent fighting with the FARDC. Madelaine and her nine children came to Lulingu after the Interahamwe brutally murdered her husband. One of her daughters and her husband then died to illness and conflict, respectively, so Madelaine was left to care for their orphans as well. Jan., 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Villagers and family members mourn at the funeral of his murdered 7-year old son, Damas. The belief in sorcery includes a dogma that a rope used to commit suicide has inherent powers; the rope can be sold in markets in Burundi and Tanzania for thousands of dollars to believers that claim it will give them black magic powers. Damas' murder was staged to appears a suicide by hanging. Jan. 18, 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A child sits on a pice of old mining equipment in a colonial building that speaks to the history of the Lulingu area. The structure was originally built by Belgian colonials as part of their mining enterprise in Lulingu. Names, drawings and phrases scraped into the surface of the walls reveal another history-- it was later converted into a prison by FARDC when they were still operating in the area. The Raia Mutomboki chased out the FARDC last year, accusing them of being the same group as the Interahamwe, an accusation rooted in criticism of the Congolese government's demobilization policies in which former rebels are offered higher ranks within the congolese army. Nowadays, the building is used to house a primary school. Jan., 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Decaying Belgian colonial era structures speak to the area’s history of mining, and to Congo’s struggles with outsiders who vied for its riches. Lulingu was a central site for Belgian colonial mining operations until the 1960s. After independence, the Belgians returned as contractors and remained in the area until 1988. It is one of the two biggest points in the province for cassiterite mining, and was thus a key site for mining during Belgian colonial times. The town still benefits from certain infrastructure set in place by the colonial enterprises, such as very basic electrical power lines and a river dam. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Migrants from the Bashi tribe of Bukavu region provide labor for the mines in territory controlled by the Raia Mutomboki. The Rega tribe, which make up the RM, are able to play supervisory roles due to their unique technical knowledge on the mining industry gained from laboring under the Belgian colonial enterprises of the past. Dec., 2013. South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A traditional ceremony takes place outside the home of Lulingu’s King Asani Keka Mbezi. The Raia Mutomboki’s members are ethnically part of the Lega tribe, known for its intact traditions and witchcraft. The arrival of colonial Belgian powers and its western missionaries wiped out most traditions in Congo. The remoteness of the Lega peoples, however, who inhabit the jungle areas in the east, allowed for the survival of their traditions. Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In a Catholic church, a couple walks down the aisle during their marriage ceremony. A normal sight in other parts of the world, in Lulingu, this offers a testament to the sense of relative security felt by villagers. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

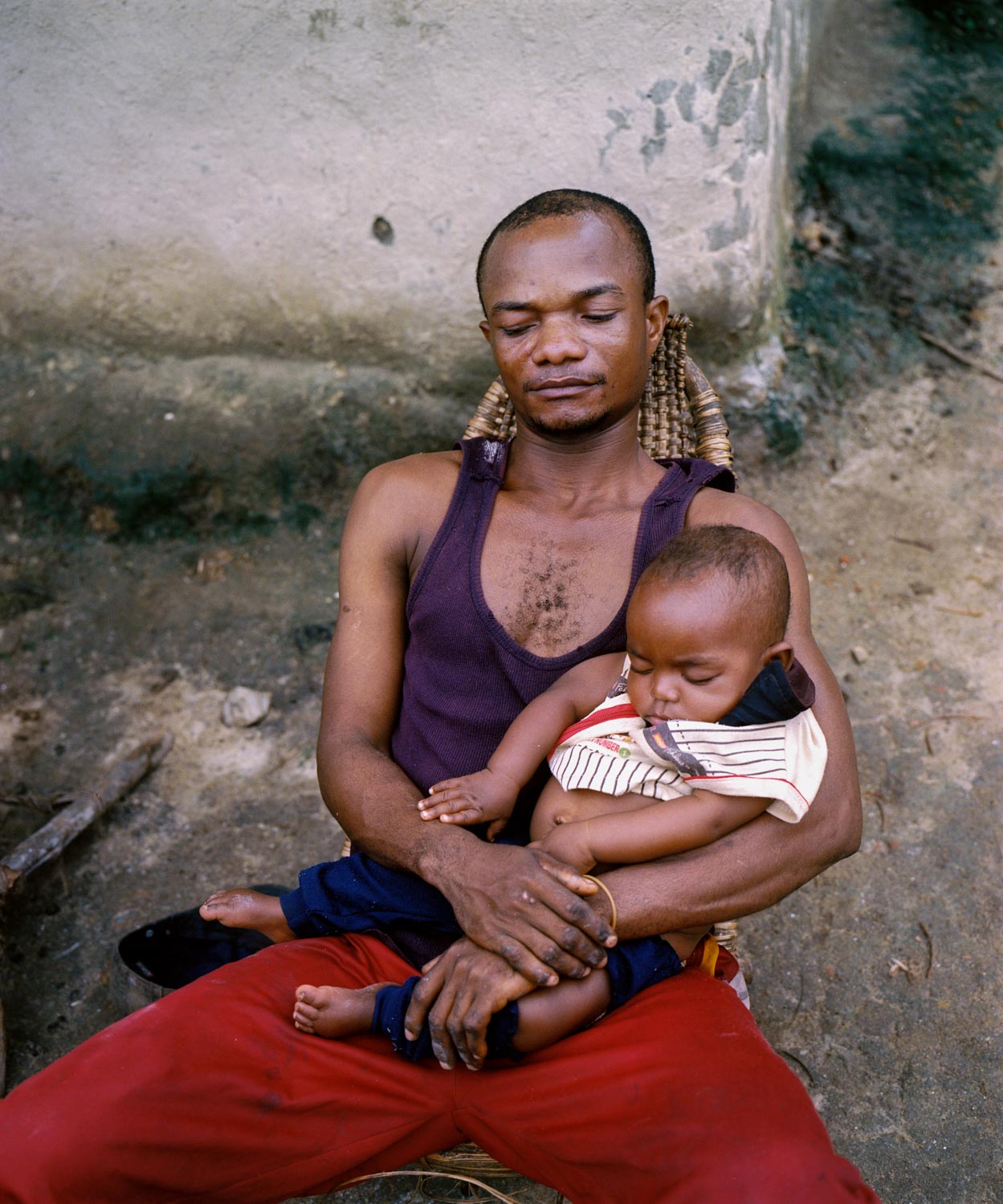

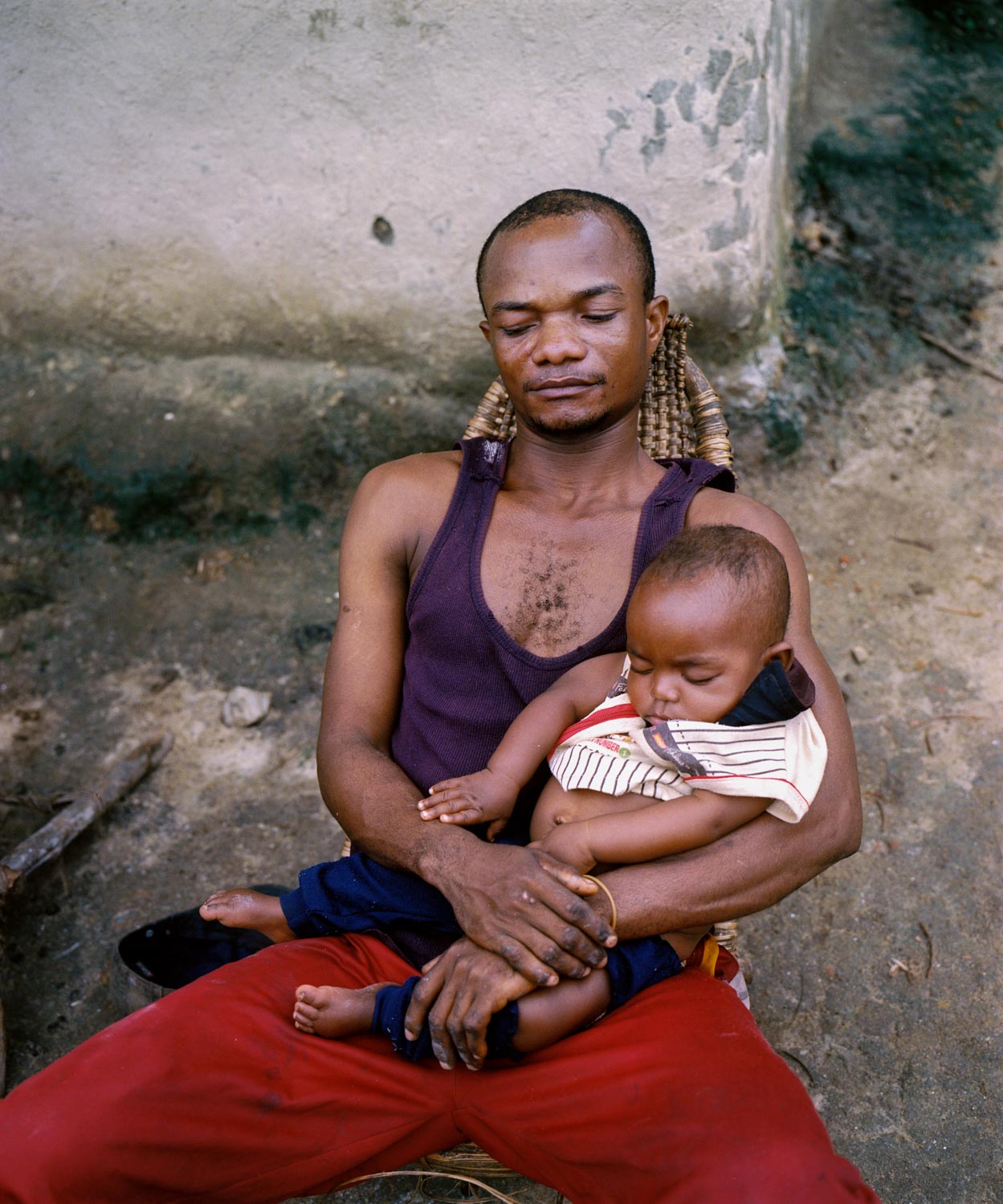

Major Bamwizio Kilumbalumba Wamenya sits with his child, outside his home. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On New Year's Eve, a roadside sign reads, "2014, what shall we say again? We ask for lasting peace." Dec. 31, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Decaying Belgian colonial era structures speak to the area’s history of mining, and to Congo’s struggles with outsiders who vied for its riches. Lulingu was a central site for Belgian colonial mining operations until the 1960s. After independence, the Belgians returned as contractors and remained in the area until 1988. It is one of the two biggest points in the province for cassiterite mining, and was thus a key site for mining during Belgian colonial times. The town still benefits from certain infrastructure set in place by the colonial enterprises, such as very basic electrical power lines and a river dam. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Raia Mutomboki ranks include women and minors, allegedly enlisted voluntarily. Mari, now 18 years old, joined the Raia Mutomboki as a soldier when she was 16 years old. At the time she had already lost her entire family to the conflict. She soon married a fellow soldier whose family had suffered a similar fate. They now have a son together. Dec. 27, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government administrator, hosts a town meeting alongside traditional and Raia Mutomboki leaders inside a decayed building from the Belgian colonial era. The Raia Mutomboki insist they should not be labeled “rebels” like other armed groups operating in Congo, citing that they have not interfered with the work of government officials in their territory. Dec. 28, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Raia Mutomboki fighters gather, wearing leaves for camouflage, after going on a patrol through Lulingu’s surrounding areas. The group claims that they derive their power from the Dawa, a magical bracelet worn around their upper arms. The power comes from Kimbirigiti, a forest spirit that they invoke through their elders when there is an enemy. As long as they respect the rules not to rape or steal, Kimbirigiti will render them invincible to their enemies. Dec. 27, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A young boy stands by a reservoir in the dense jungles just outside Lulingu, a remote village in South Kivu. The jungles are littered with mining sites and various armed groups. Dec., 2013. South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Seated in her office, Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government Administrator, explains her position vis-a-vis the Raia Mutomboki. Herself a victim of the abuses of both the Interahamwe and the Armed Forces of the DRC, she says she is happy with the security the RM have brought to the area. Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Graffiti on the walls of the home of Henriette Useni Kabake, Lulingu's government Administrator, testify to a time when FARDC soldiers forcefully occupied her home for over a year, throwing out her children. At the time she was hospitalized in Goma due to injuries from a moto accident. After they were defeated by the RM, the FARDC left Henriette's home and the area, first looting all of Henriette's valuables that were in her home. Jan. 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Widow Madelaine Kapinga stands outside of her makeshift home in a part of Lulingu town that is occupied by people displaced by the conflict. Her story is not an uncommon one in the area, where most have lost family to massacres committed by the Interahamwe or in subsequent fighting with the FARDC. Madelaine and her nine children came to Lulingu after the Interahamwe brutally murdered her husband. One of her daughters and her husband then died to illness and conflict, respectively, so Madelaine was left to care for their orphans as well. Jan., 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Villagers and family members mourn at the funeral of his murdered 7-year old son, Damas. The belief in sorcery includes a dogma that a rope used to commit suicide has inherent powers; the rope can be sold in markets in Burundi and Tanzania for thousands of dollars to believers that claim it will give them black magic powers. Damas' murder was staged to appears a suicide by hanging. Jan. 18, 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A child sits on a pice of old mining equipment in a colonial building that speaks to the history of the Lulingu area. The structure was originally built by Belgian colonials as part of their mining enterprise in Lulingu. Names, drawings and phrases scraped into the surface of the walls reveal another history-- it was later converted into a prison by FARDC when they were still operating in the area. The Raia Mutomboki chased out the FARDC last year, accusing them of being the same group as the Interahamwe, an accusation rooted in criticism of the Congolese government's demobilization policies in which former rebels are offered higher ranks within the congolese army. Nowadays, the building is used to house a primary school. Jan., 2014. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Decaying Belgian colonial era structures speak to the area’s history of mining, and to Congo’s struggles with outsiders who vied for its riches. Lulingu was a central site for Belgian colonial mining operations until the 1960s. After independence, the Belgians returned as contractors and remained in the area until 1988. It is one of the two biggest points in the province for cassiterite mining, and was thus a key site for mining during Belgian colonial times. The town still benefits from certain infrastructure set in place by the colonial enterprises, such as very basic electrical power lines and a river dam. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Migrants from the Bashi tribe of Bukavu region provide labor for the mines in territory controlled by the Raia Mutomboki. The Rega tribe, which make up the RM, are able to play supervisory roles due to their unique technical knowledge on the mining industry gained from laboring under the Belgian colonial enterprises of the past. Dec., 2013. South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A traditional ceremony takes place outside the home of Lulingu’s King Asani Keka Mbezi. The Raia Mutomboki’s members are ethnically part of the Lega tribe, known for its intact traditions and witchcraft. The arrival of colonial Belgian powers and its western missionaries wiped out most traditions in Congo. The remoteness of the Lega peoples, however, who inhabit the jungle areas in the east, allowed for the survival of their traditions. Dec., 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In a Catholic church, a couple walks down the aisle during their marriage ceremony. A normal sight in other parts of the world, in Lulingu, this offers a testament to the sense of relative security felt by villagers. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Major Bamwizio Kilumbalumba Wamenya sits with his child, outside his home. Dec. 29, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On New Year's Eve, a roadside sign reads, "2014, what shall we say again? We ask for lasting peace." Dec. 31, 2013. Lulingu, South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo.